Vedanta, which comes from the Sanskrit words ‘Veda,’ meaning knowledge, and ‘anta,’ which means end or conclusion, is one of the most profound and most intellectually rigorous philosophies to have emerged from ancient India. It is the philosophical endpoint of the Vedas, the ancient and sacred Hindu scriptures; thus, the name ‘Vedanta’ is often translated as ‘the end of knowledge’ or ‘the ultimate knowledge.’

Vedanta is not so much a system of philosophy as it is a way of life. It’s a spiritual philosophy that promotes the godliness of humanity, the eternal life of the soul, and the unity of being. It’s a philosophy that seeks human transformation through insight.

Vedanta philosophy originates from the Upanishads, a segment of the ancient Hindu texts. These are the actual Vedanta teachings, which the Upanishads discuss: Brahman (the ultimate reality), Atman (the individual soul), and the relationship between Brahman and Atman. The canonical texts of Vedanta are the Upanishads, the Brahmasutras, and the Bhagavad Gita, collectively referred to as the ‘Prasthanatrayi.’

Brahman, in Vedanta, is the ultimate reality, the absolute, universal soul. It is endless, everlast, immutable, and inseparable. It is outside time, space, and causality. Brahman is not an object of knowledge, but the very subject, the very basis, of all knowledge. It is not something that the senses or intellect can comprehend, but rather something that can only be realized through direct intuition.

Atman in Vedanta is the individual soul, the true self. It is the soul of man, the imperishable spirit. Atman is nothing but consciousness, bliss, and existence. It is not subject to bodily conditions or psychological states. Atman is the observer, the experiencer, the core self that witnesses everything yet remains untouched.

The essence of Vedanta is that Brahman and Atman are identical. Atman is Brahman. This is the Upanishads’ great proclamation, Tat Tvam Asi (That Thou Art). The seeming distinction between Brahman and Atman is ignorance (Avidya). When this ignorance is dispelled by knowledge (Vidya), the self [Atman] reveals itself as Brahman.

Vedanta philosophy is further divided into three schools, which interpret the texts of the Prasthanatrayi in their own unique ways. These are Advaita (nondual), Dvaita (dual), and Vishishtadvaita (qualified nondual) Vedanta.

Advaita Vedanta, as propounded by Adi Shankaracharya, asserts that there is only one reality, Brahman, and everything else is an illusion (Maya). It stresses the unity of existence, the identity of Brahman and Atman. When this oneness is realized, it is liberation (Moksha) according to Advaita. Advaita Vedanta is probably the best known of the three in the West.

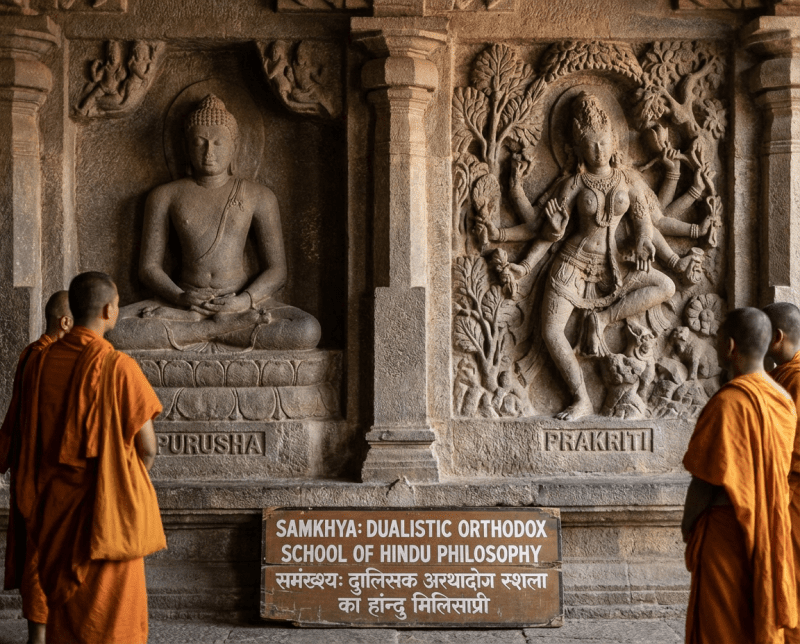

Dvaita Vedanta, founded by Madhvacharya, is a dualist philosophy. It preserves the distinction of the soul and Brahman. In Dvaita, individual souls are dependent on Brahman, and liberation is attained through devotion to God.

Ramanujacharya founded Vishishtadvaita Vedanta, a qualified nondualistic school of thought. It states that the individual soul and the material world are real, yet they are also part of Brahman. For Vishishtadvaita, moksha is found through surrender to God’s grace.

Vedanta has left a deep impression not only in India but also in the West. It has influenced numerous intellectuals, philosophers, and gurus worldwide. Its timeless lessons have resonated with people of all faiths and backgrounds.

In summary, Vedanta is a philosophy that offers a comprehensive perspective on existence. It’s not airy philosophy; it’s a guide to a meaningful existence. It instructs us to turn inward, to identify with our innate divine nature, and to exist in harmony with nature. Believer or skeptic, theist or atheist, Vedanta has something to say to all.

Upanishads (Oxford World's Classics Edition)

translated by Patrick Olivelle

Product information

$7.87 $5.24

Product Review Score

4.76 out of 5 stars

197 reviews