Through culture and millennia, the human spirit has been wrestling with a reality that transcends the immediately tangible. This “beyond,” this realm beyond the reach of our senses and our reason, is what we call the “transcendent.” Religions in their variety provide avenues to approach this transcendent reality, to anticipate a union, a communion, a merging with its might and essence. Grasping this idea means threading your way through a dense weft of faiths, rituals, and esoteric epiphanies.

Different religions express the transcendent differently. Common threads of ultimate truth, divine force, and a link to something beyond oneself are always present. For the Abrahamic faiths – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – the transcendent is frequently embodied in a single, omnipotent God. Union with the transcendent, then, becomes a profound personal connection with this deity. In Judaism, this bond is nurtured through mitzvot, prayer, and study. It’s not a mystical merging, but a covenant relationship marked by obedience, devotion, and a pursuit of righteousness.

Christianity emphasizes a more personal union through faith in Jesus Christ. This union goes beyond purely ritual. It is a transformation of the self, a rebirth by grace, marked by love, forgiveness, and communion with God in one’s life. Christian mystical traditions, from Meister Eckhart to St. John of the Cross, depict a deeper union—an experience of mystical absorption in the divine—a state of “kenosis” or a “dark night of the soul” that precedes illumination.

Islam likewise depicts an intimate connection with God (Allah) as the objective. By submission (Islam) to God’s will, articulated in prayer (Salah), charity (Zakat), fasting (Sawm), and pilgrimage (Hajj), Muslims aim to bring themselves nearer to God. Sufism, the mystical branch of Islam, seeks a more immediate union with God through contemplative and spiritual exercises designed to experience the divine within. This experience, known as “fana” (the annihilation of the self in God), results in a state of “baqa” (subsistence in God).

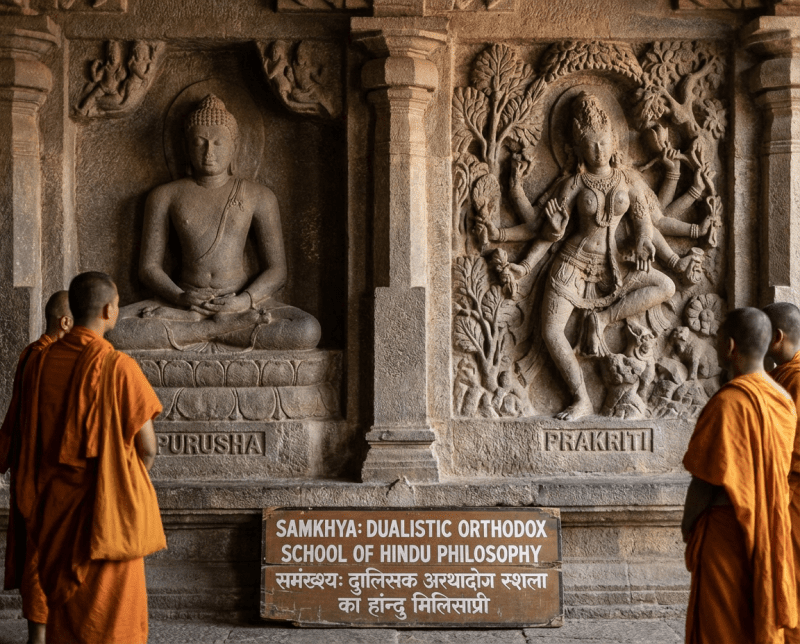

Eastern religions offer alternative views on the transcendent. Hinduism, in its various schools, views the transcendent as Brahman. Union with the transcendent, or moksha, is freedom from reincarnation, attained through paths such as devotion, knowledge, and selfless action. The specific character of this union differs from school to school, with some advocating a union with Brahman, while others advocate for blissful awareness.

While not advocating a creator God, as in the Abrahamic religions, Buddhism also recognizes a transcendent reality – Nirvana, the state of liberation from suffering and the cycle of rebirth. To attain Nirvana is to quench desire and clinging through meditation and mindfulness. A feeling of deep peace, serenity, and freedom from the ego typically characterizes this state of being.

Taoism centers on aligning yourself with the Tao, the fundamental order of the cosmos. Union with the transcendent, according to Zhuangzi, doesn’t come from any religious rites, but rather from living according to the ‘Way’, embracing simplicity, and nurturing inner peace. This focus on natural and effortless distinguishes Taoism from more theistic traditions.

Ultimately, the nature of the transcendent and the path to union differ dramatically among religions. A common thread unites them all—the desire to connect with something significant and beyond the ordinary realm of existence. This quest, what we call spiritual, brings comfort, purpose, and a deep sense of communion with the cosmos and God, however that is defined within each religion. The various forms of this pursuit reveal the persistent human desire to escape the confines of our mortal lives and find a deeper connection to something greater.

The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry Into the Non-rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and Its Relation to the Rational

by Rudolf Otto

Product information

Product Review Score

4.2 out of 5 stars

32 reviews